Today, this is especially true in industry verticals such as big-box retail, grocery and wholesale distribution, where it is common to have private and/or dedicated fleets servicing a retail/store network.

In these verticals, the inbound and outbound networks operate in fundamentally different ways. While trucks are still the most common means to move products, that is about the only commonality, since processes, organizational structures and systems vary by network type.

In this document, we will explain the challenges of coordinating these functions and what you can do to make it happen.

“ There is no “silver-bullet” technology solution”

Primary Versus Secondary Network Transportation

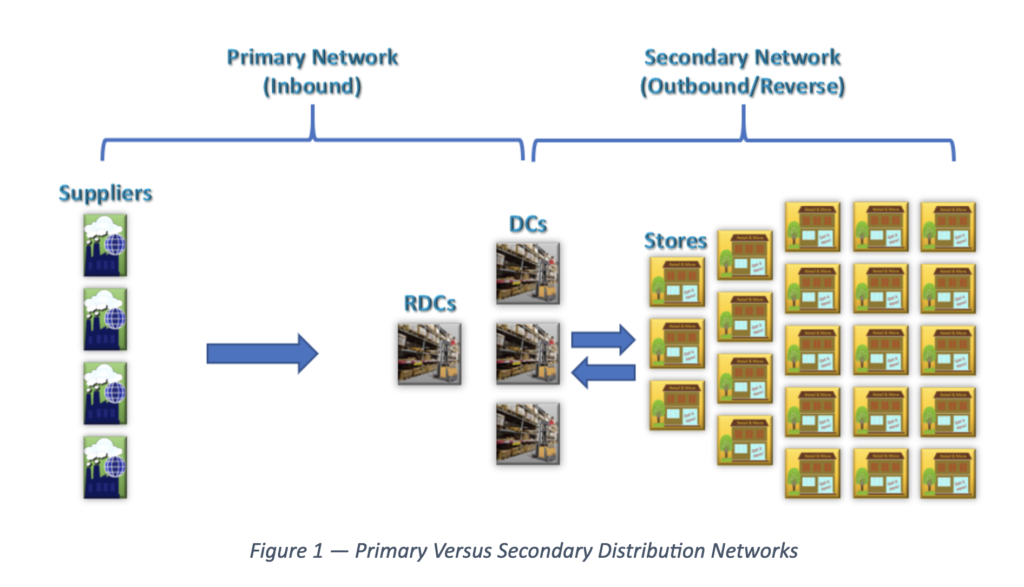

Moving forward, the terms primary and secondary network (versus inbound and outbound) will be used, as they better articulate the difference in the transport problems we are looking to solve.

Inbound and outbound are relative terms defined by the point of view of the shipper. For instance, a full TL moving from a supplier to a retail DC is an outbound move for the supplier, but an inbound move to the retailer. However, both are considered primary network moves. (See Figure 1)

Varying Planning Objectives

Historically, transportation organizations have, through necessity, employed different solutions and strategies when managing primary and secondary networks. While there are opportunities for crossover planning (e.g., backhauls), it is important to recognize the ways in which these two planning spaces differ before identifying a solution.

Both planning environments seek cost minimization, yet the cost assessment is inherently different for primary and secondary transport. The levers used to manage primary network transportation include:

- Order consolidation

- Mode selection

- Multi-stop TL formation

- Carrier selection/routing guide compliance

- Service level selection (standard versus expedited)

- Through point determination (should the order flow through an intermediate consolidation point or go directly to the consignee)

“ Customers not only want a widget, but they want it delivered to them at a given time and in a given manner.”

Conversely, a fleet-centric secondary network solution strives to minimize waste—to avoid underutilization of owned assets in a private fleet operation or committed assets of a dedicated fleet. Fleet routing solutions do this by building cost-efficient routes that minimize miles while adhering to service and operational constraints inherent to the secondary network problem, e.g., customer time windows, vehicle restrictions and hours of service.

These two network types therefore require fundamentally different logic to solve transport problems in an efficient manner.

Limited Planning Horizon Overlap

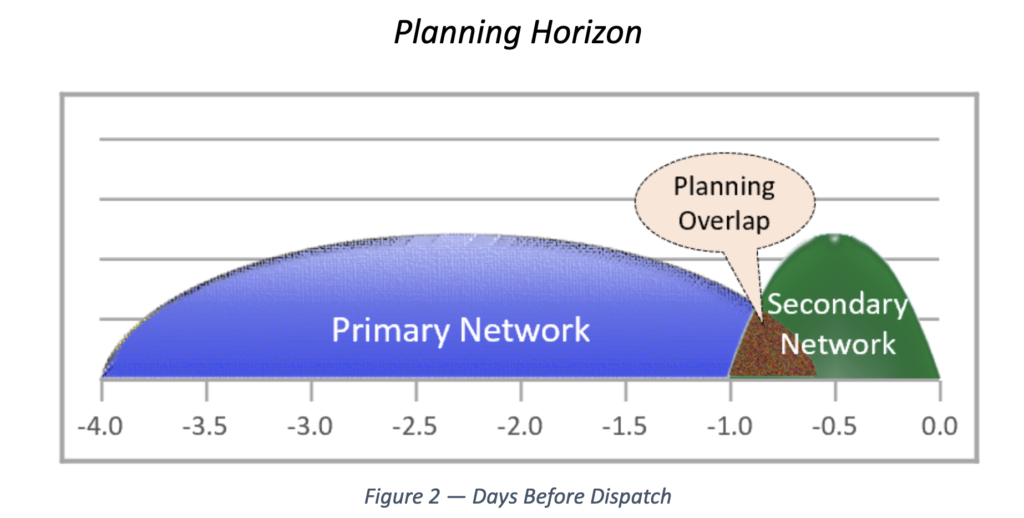

Another significant obstacle to integrated planning may be the discrepancy between the planning horizons of the primary network versus the secondary network. Figure 2 illustrates the typical planning horizons associated with each network.

Primary network orders might be planned several days (or weeks, as in the case of ocean transport) in advance, whereas in the secondary network, orders might be planned only a day in advance of the delivery.

“Developing the right integration strategy can ensure your overall transportation solution set is equipped to properly handle your multiple logistics challenges.”

Geographic Granularity

The primary network is typically made up of long-haul freight. These solutions use postal code-/zip code-based mileage calculators to estimate and normalize distances. Understanding the underlying street network is not required for primary network planning; it would require overhead that is of limited value.

However, in the secondary network, actual miles, travel times and travel paths play a significant part in how loads are planned. For example, planning a 10-stop route in Chicago requires the optimizer to understand traffic patterns by day of week and time of day, one-way streets, vehicle restrictions and accurate facility location information (i.e., street-level geocoding). This is a much more granular understanding of road systems and traffic patterns as compared to what would be required in planning a full truckload going a much longer distance, e.g., from Los Angeles to New York.

Asset Utilization

When using one-way carriers (e.g., TL, LTL, Parcel, Ocean), how well the asset is used is not (explicitly) the shipper’s concern. This headache is purely the carriers’, which are responsible for minimizing their asset’s empty miles and enhancing margins through careful construction of their networks (i.e., which lanes and shippers a carrier agrees to haul for).

However, an asset-based shipper operating in the secondary network is saddled with many of the same problems as an asset-based carrier. These shippers must plan for all miles, loaded and unloaded. But private fleets are typically judged on their primary mission (delivery service) versus revenue generation or empty miles reduction.

The private fleet is an extension of the shipper’s product offering. Customers not only want a widget, but they want it delivered to them at a given time and in a given manner. Empty mile reduction through internal or third-party backhauls is desirable, but it must be done in a manner that does not impact the primary mission of the fleet.

What can you do today?

There are opportunities to have a coordinated logistics system that is built cognizant of primary and secondary network synergies. For instance, when planning inbound loads, understanding where your fleet assets are likely to terminate is a good place to start.

This understanding will enable the product procurement team (aka Buyers) to place supplier orders in a manner that aligns with outbound fleet operations. While simply being in the right geography is a good start, there are other considerations that also need to be considered, such as the driver’s hours of service, the supplier’s ability to efficiently load the trailer and whether the trailer has capacity not consumed by dunnage and/or store returns.

Identifying these opportunities requires bringing both sets of business knowledge and expertise together into the same discussion. Developing the right integration strategy can ensure your overall transportation solution set is equipped to properly handle your multiple logistics challenges and position your organization to find new opportunities across your combined transportation arena.

Conclusion

In summary, there is no “silver-bullet” technology solution. This increases the challenge, but also the reward. So, as you look to address this issue, think about the following:

- Strive to be a leader

Keep your eye on the movement of technologies, particularly in the area of high-dimensional algorithms used for machine learning and artificial intelligence.

- Be creative

Assess your current overall distribution network. Look for lost opportunities and identify ways to turn them into profitable activities.

- Be proactive

Examine the current state of your transportation operations relative to the industry at large. Refresh older solutions to ensure you have access to the latest cost-saving features, technologies and innovations.

- Stay engaged

Keep lines of communication open between the different planning teams in your organization. Foster a collaborative organizational culture that strives to identify forward-thinking opportunities.

Bernadette Harmon is a senior solution architect at JBF Consulting with expertise in private fleet routing and scheduling, mapping technologies, and transportation consulting that spans 30 years. Her experience includes full lifecycle product development, from requirements gathering and analysis and business process definition through implementation, using standard and agile methodologies for global food service distributors, international grocery/retailers, home healthcare, and more, spanning six of the seven continents.

About JBF Consulting

Since 2003, we’ve been helping shippers of all sizes and across many industries select, implement and squeeze as much value as possible out of their logistics systems. We speak your language — not consultant-speak – and we get to know you. Our leadership team has over 70 years of logistics and TMS implementation experience. Because we operate in a niche — we’re not all things to all people — our team members have a very specialized skill set: logistics operations experience + transportation technology + communication and problem-solving skills + a bunch of other cool stuff.